The Machine Elves’ Shoes builds a world in which childlike bliss and dark forces revel together. Where doors keep opening to new experiences of psychedelic consciousness. Where the trash stratum sparkles and elves dance on at an endless rave party.

Raving in the infinite trash stratum

By Laura Skerlj

In Phillip K. Dick’s Exegesis – a publication of the science fiction writer’s journal extracts from his final years – he professes his attraction to trash. Everyday waste, refuse, detritus. In Dick’s novels, this lowly genus of material

is fertile ground for an apophatic spiritual connection, where enlightenment is sought in the negated instead of the pure and sacred. Where, if one changes their percep- tion, they might find God (or spirituality) in the stratum of “worthless” garbage that culminates unfavourably in riverbeds, alleyways, drains, bedrooms, tips, oceans, oppor- tunity shops, random kitchen drawers and hard rubbish collections. It is here, in the trash, that Dick found clues remnants of a “sociological drift” where dense histories of rejection accumulate and transform into new composi- tions of odd, vital and joyous life.

In Berlin-based artist Emily Hunt’s exhibition The Machine Elves’ Shoes, highly crafted ceramic figurines – elfish in appearance, dressed in psychedelic dreamcoats and heavily patterned accessories – occupy a symbiotic, fantastical world. Flushed in symbols from a mysterious language, the gallery is transformed into an enchanted zone where colours clash, patterns reproduce, culture is counter and hierarchies are upturned. The psychedelic aesthetic of Hunt’s universe is unlocatable and shifts in time and space in a mash-up of (possible) new age, rave, cyber, nineties, Baroque and hallucinogenic traditions; we don’t know where Hunt’s figures come from but, as Dick profoundly states, “The symbols of the divine initially show up at the trash stratum,” and it is there that they

can be found – dancing, replicating, scheming, chatting

in symbols, opening and closing doors, shifting between worlds.

Put on your red shoes

Based on Hans Christian Andersen’s grody 1845 fairy tale The Red Shoes, the 1948 British technicolour film of the same name includes an exquisite 17-minute ballet sequence that is a direct “impressionistic link” to the original. In Andersen’s version, a young girl acquires a pair of glitzy red shoes which she refuses to take off, even in inappro- priate circumstances. The shoes themselves have magical powers, as the girl cannot stop dancing when she wears them. Disregarding the instructions of her guardians (and even an angel who tells her to take the shoes off, stop dancing and attend her foster mother’s funeral), the shoes’ power grows and soon the girl is at their mercy – dancing, dancing, dancing. To stop them, she orders an executioner to cut off her feet. However, the shoes, with her bloody amputated feet inside, keep dancing and the girl is left horrifically crippled.

In the film’s ballet sequence, the young girl is instead a young woman – an adored and ravishing red-haired ballerina who purchases a pair of blood-red ballet slippers from a junkie-esque shoemaker. Grey in the face, with

a sweaty bob of unruly hair under which his eyes flicker manically, the shoemaker is delighted that the ballerina has chosen to wear his shoes and experience the intoxi- cation he knows they will bring. Soon, she is dancing like never before, without the constraints of choreography or balletic tradition; her sensuality is set free as she passion- ately frolics through the city. However, as she dances, downtown mutates into a hellish and empty underworld – a trash stratum. Her boyfriend, friends and other towns- folk combust into papery versions of themselves and float down, deflated, to the ground in a confetti of lost souls. Pushing through the purgatory of the new world she now inhabits, she dances on under the influence of the red shoes, euphoric, addicted and alone – a tarantism that leads her from mediocrity through ecstasy, before pushing through the repression barrier to someplace so vacuous that all meaning is lost. Finally, after a flamboyant caper with the shoemaker, she summons a priest to remove the slippers and, with her supply cut off, collapses into death. The shoemaker snatches up his rouge-coloured beauties and jostles devilishly back to his store, awaiting the next pleasure seeker.

In Hunt’s exhibition, an unoccupied ceramic ballet shoe waits on a shelf, inscribed with the word “FEVER,” bulging in pills and the magical number 3-3-3, among other psychedelic symbols.

Everything all of the time

In the traditions of ballet and opera, the artistic work does not stop at choreography: the set, costumes, musical score, architecture, lighting and accompanying publications all become part of the holistic production. In 1849, Wagner described this holism as a gesamtkunstwerk, which rough- ly translates from German to a “total work of art,” where different art forms are combined to create a cohesive whole. In The Machine Elves’ Shoes, Hunt revels in the God-like power of creating an entire world – figures of various shapes, sizes and characters; ceramic costumes em- bossed in symbology; the architecture the figures inhabit; various portals. Also, a hand-painted alphabet – so detailed it reveals itself slowly through intricate illustrations of dainty-but-grotesque imagery, notes to self and bacterial flora – hangs on the wall. (In the near future, we learn that Hunt transforms this alphabet into a Ouija board, a com- munication device not unlike the one used by poet James Merrill (1926–1995) to channel his 560-page apocalyptic poem The Changing Light at Sandover.)

In Hunt’s world, decoration moves, slippery, across figures and objects and surfaces like a spreading disease or a repeated DNA imprint of a fantastical culture. Within this decoration, portals open and close to let spirits in and spirits out, and there is not much room to breathe. Actually, there is no space at all; when one stops to seek refuge, visions rush forward, like in a trip. The infinitism of this decoration recalls the complex works of British artist Madge Gill (1882–1961) – a major influence for Hunt – whose images feature densely wrought pat- terns of wide-eyed women’s faces, checkerboard details and wing-like flourishes. After the sad passing of one of her sons and the stillbirth of her daughter, Gill turned to drawing as a way to connect with her lost children in another realm. However, these works were not led by Gill, but by her spirit guide, Myrninerest, of whom she was,

or believes to have been, spiritually possessed. Through Myrninerest, Gill channelled innumerable pictures,

each one an example of horror vacui through its dense mark-making and pattern – the threat of empty space more acute than a claustrophobic flow of forces.

“But what do you do with an elf?”

In July 1989, DJ and producer Dr Motte put on Berlin’s first Love Parade – a techno dance festival of 150 people in West Berlin’s Kurfürstendamm avenue. But the par- tyers who danced downtown that day, in a demonstration registered for “Peace, Joy and Pancakes,” had no idea that Berlin would soon be reunified into an intoxicating metropolis known for its sense of liberation, artistic expression, alternative culture, sexual freedom, and of course, electronic dance music. In a glorious moment, Motte describes the night the Wall fell, when “East Ger- man devotees of club music that they could only hear on West Berlin radio crossed the border and packed into the Ufo, a renowned Kreuzberg club.” With both Berlin sides dancing together for the first time, he recalls that moment and the club culture that grew from it as dancing a “dance for a better world.”

Since then, the city’s club scene has continued to grow and evolve, gentrify yes, but keep dancing, nonethe- less. This underground is a meaningful layer of Berlin subculture that has provided many with escape, connection, reinvention and self-realisation. But the city itself is also a deeply loved trash stratum; or, as Stuart Braun described, this “city of exiles” is “an interzone.” It is well-known that troves of souls have come to Berlin from far and wide to revel in an extreme openness they could not find elsewhere. It’s also true that they frequently return time and again, often unable to leave – physically or at least in their minds.

The elfish figures in Hunt’s exhibition have been raving. For American ethnobotanist, psychedelic activ-

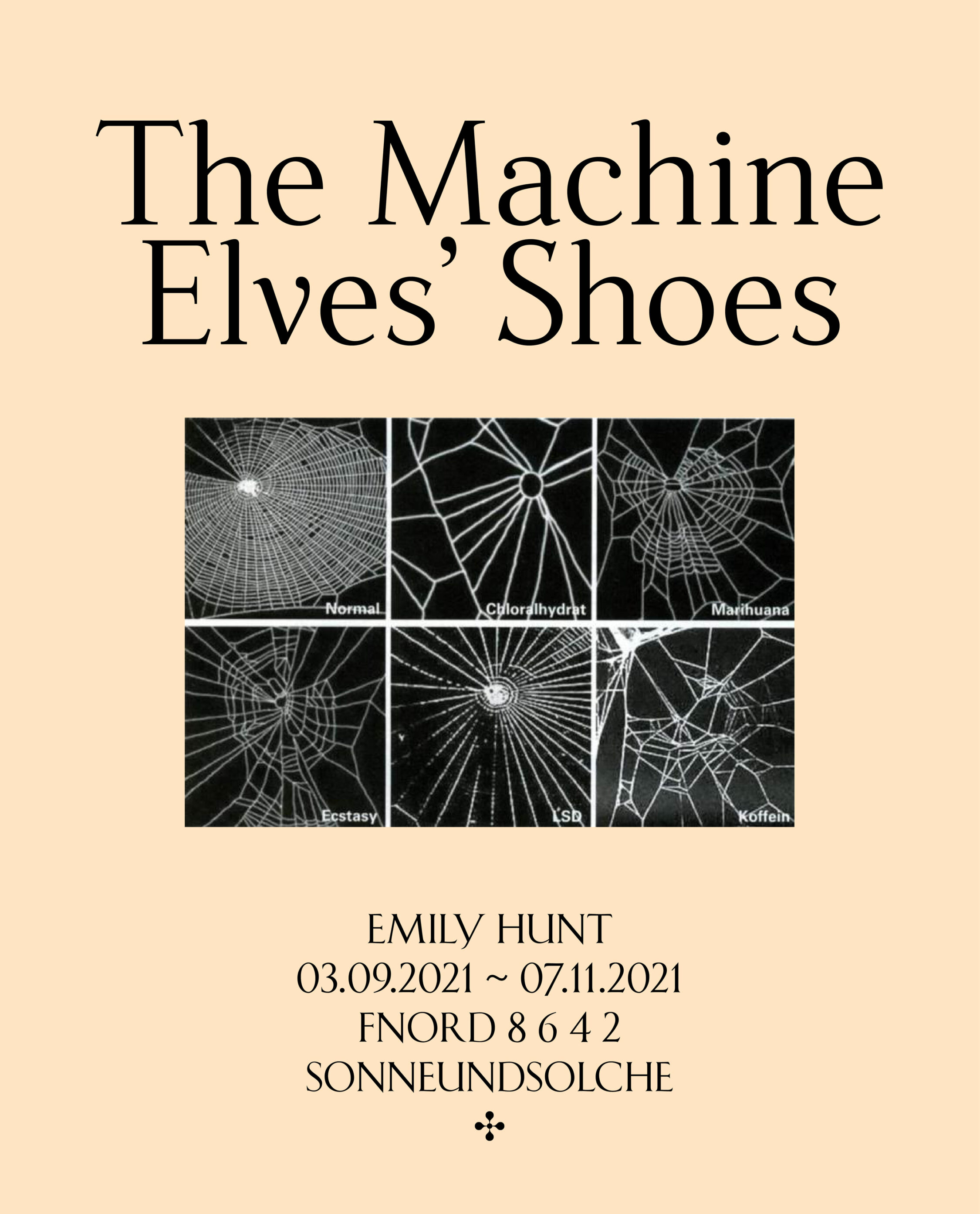

ist and mystic Terrence McKenna (1946–2000), a true experience of Dimethyltryptamine (DMT) – a powerful hallucinogen produced naturally by many plants and animals, including humans, that can inspire a fast-acting influx of visuals – is defined by the elves you meet. Made from “syntax-driving light,” these entities multiply into what McKenna calls the “self-transforming elf machine,” which is the “defining characteristic of the true DMT flash … it is not subtle, these things mob you like badly trained Rottweilers, they come bounding forward by the dozens, by the hundreds. They jump into your body; they jump out of your body.” In a video clip that layers McKenna’s audio over the top of an intense spree of convulsive psychedelic visuals, neon elf forms in various iterations – from the iconic Celtic variety to more cartoonish Bugs Bunny and Zelda sorts – roll like mercury, busy-busy, no sign of stop- ping. How much dancing is too much dancing? Accord- ing to Jung, autonomous elements can escape from the psyche and present themselves to the subject; in the DMT experience described by McKenna, the elves are what have escaped, and although they bring an overwhelming feeling of love, it’s the L-U-V kind – more crazed than comforting more synthetic than natural, more heightened than uncon- ditional, always laced in a hidden agenda. And what have these elves come for? McKenna says they’ve come to teach you their language, one seen via sound, and “they want to teach you how to do this, to transform your language. They want you to speak elfish.” According to Dr Rick Strassman, author of DMT: The Spirit Molecule, these “DMT deities” offer the tripper an exchange that is both verbal and nonverbal, with their shape or form being a vessel for language, or even language itself.

In Hunt’s exhibition – which takes its title from both machine elves and the red dancing shoes – the figures that populate the gallery space have the same self-replicat- ing quality of McKenna’s, despite each one being uniquely crafted with its own persona and probable agenda. They manifest in a way that certainly does not end with the population seen in the exhibition – there are more of these elfish figures, it seems certain, as they shift in and out of their surroundings, morphing, once an elf, then a portal, covered in portals too. They are elves but also mirrors reflecting their world and those that dare to be part of it. Here, infinitism can be found in the repetitive symbology that patterns their cloaks, hats, shoes, landscapes, bodies. Language is what they are, and meaning exists in magical solutions to everyday mundanity, restriction, conservatism or, during pandemic times, lockdown.

Sandplay

According to “high strangeness” scholar Erik Davis, it was Freud who linked the uncanny “double character” (dolls and wax figurines, for example) to animist psychology, in which all things, animated or otherwise, have spiritual life. However, as Davis emphasises, this perspective is also a feature of mystical consciousness, and is perhaps only deflated and rejected by a “modern subjectivity” in which the “liveliness of the world fails to register.” Through his anal- ysis, Davis notes that these double characters (the doll-like ballerina in The Red Shoes, McKenna’s DMT elves, Hunt’s figurines) can be located within “an eerie animation.” It is within this framework that Hunt’s constructed, fantastical world is well-placed. All her dualisms are at home here: the micro and macro; the human and nonhuman; fiction and science fiction; real-life and animation; love and LUV.

This world, but also the artist’s creative process, can be understood via Jung’s Sandplay therapy: here, two trays are filled with sand – one dry, one damp – and the patient can place a variety of miniatures in the sandboxes to create a three-dimensional scene or image. The idea is that by allowing the imagination to freely associate, the patient can process real and often traumatic experiences through a playful method that bypasses the analytical brain in order to access the unconscious. In turn, the sandbox becomes a safe space for the psyche to express itself. But what happens in the sandpit, what energy builds there, when your cute-looking miniatures come from complex places? What happens when play is both joyous and addictive, like dancing when you don’t quite know how to stop? Hunt’s exhibition The Machine Elves’ Shoes builds a world in which childlike bliss and dark forces revel together. Where doors keep opening to new experiences of psychedelic consciousness. Where the trash stratum sparkles and elves dance on at an endless rave party.