The image of an empty sofreh has long been used by Iranian people in peaceful protests.

Sofreh traditionally refers to an iconic Persian fabric that is spread on the ground for eating or used as a backdrop for seasonal feasts and celebrations. Over time, the term itself has taken on a larger cultural significance, referring to concepts of gathering and sharing a place for family and friends to come together. In virtually all ancient civilisations, especially in the Middle East, sewing and knitting clothes and household items (furniture, utensils and decorative objects for domestic use) was predominantly a women’s occupation. Persian carpet weaving, one of the most highly regarded crafts, is the result of the labour of women and girls sitting behind a loom for months or even years. Kalamkari fabrics, a type of handpainted or blockprinted textile perfected in the seventeenth century by the Isfahan chintz industries, were often ornamented with arabesque patterns. Before the advent of mechanical tools and industrial weaving techniques, needlework, zardozi, sofreh, quiltmaking, chintzing, dyeing, beadwork and wickerwork were the main source of income for Iranian women. They provided extra earnings for households from the Caspian Sea to the Persian Gulf, in different regions with various cultures, languages and dialects.

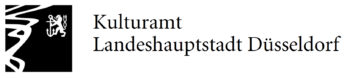

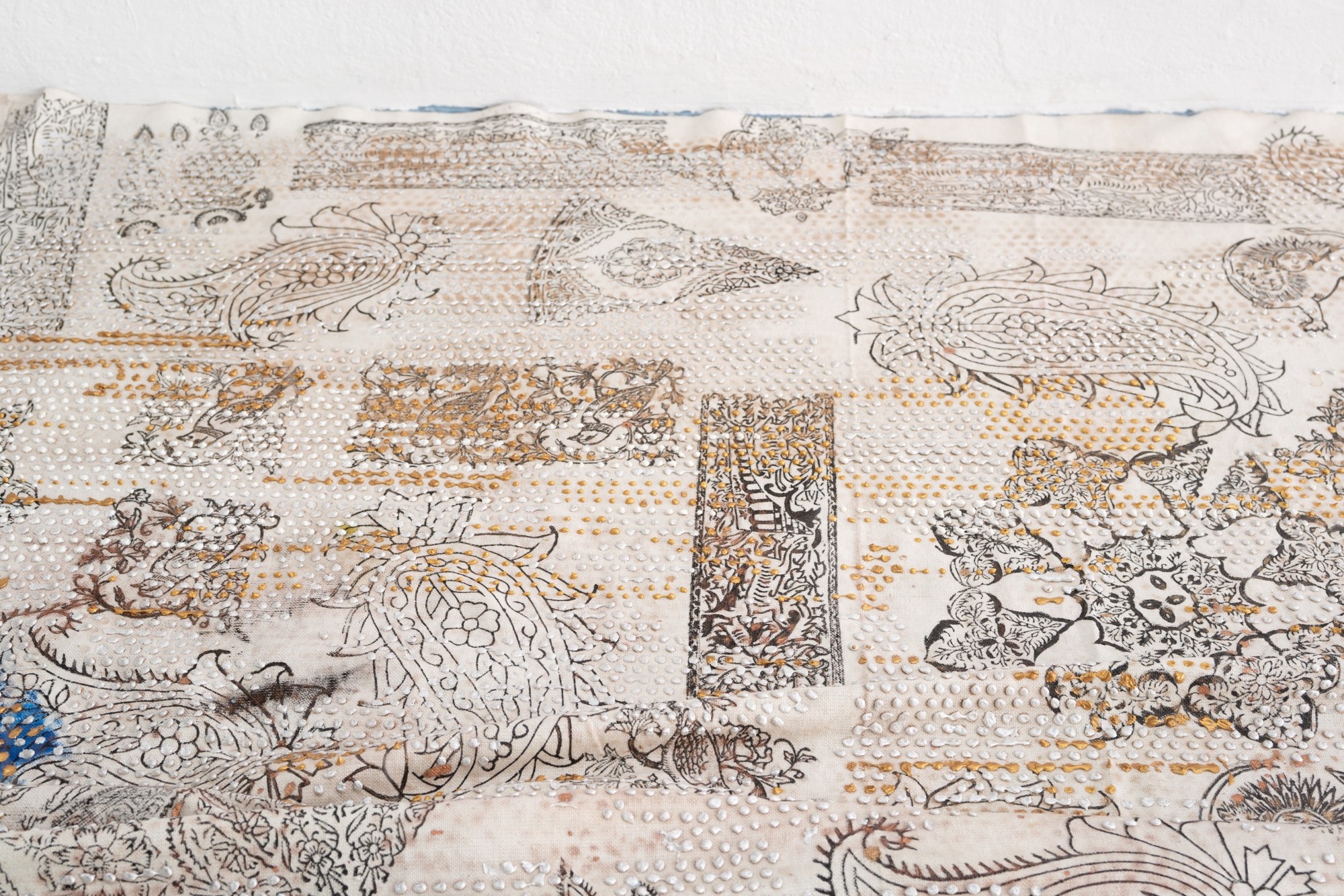

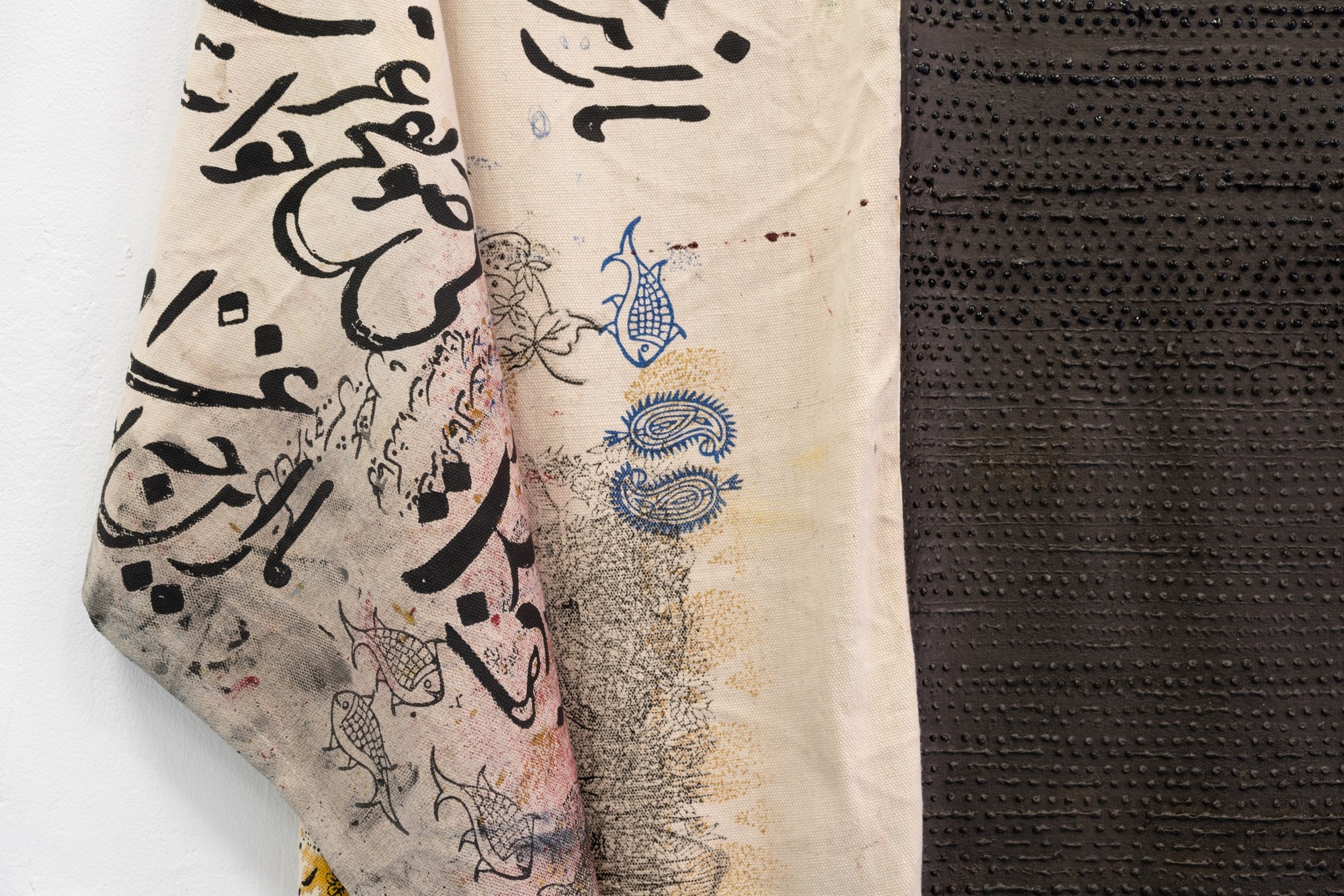

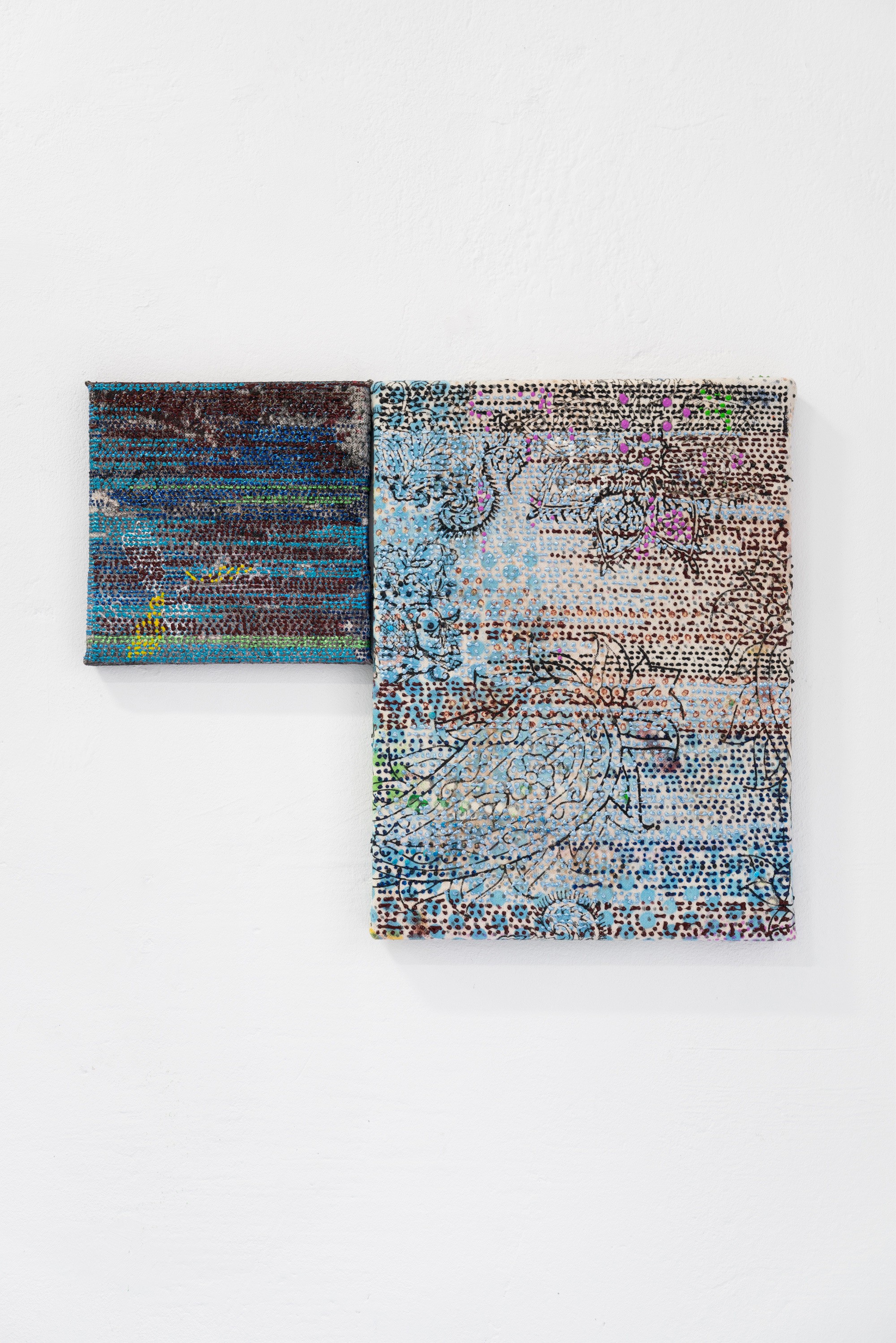

Hodaei’s latest series, Spread Fabrics, is made of cotton fabrics used in kalamkari, which are typically painted with natural paints, in this case pomegranate peel. Kalamkari artists initially used wooden stamps to decorate fabrics known as takht-e-shaal. Their experimental and sometimes unfinished motifs were miniatures and arabesque floral patterns as well as hunting, battle and festive scenes or depictions of mythological stories from the Shahnameh and other Iranian epic poems. Hodaei uses the pieces of cloth and their asymmetrical and unfinished shapes as the background of her works. She either blackens these spreads with pitch or oil, or uses them as canvases for stories from her everyday life, executed in her trademark pointillist style. Besides kalamkari spreads, Hodaei’s installation uses rice and flour bags whose content has been removed. Still bearing their brand names, these empty containers symbolise poverty, much like the old, greasy gloves in her installations.

The image of an empty sofreh has long been used by Iranian people in peaceful protests. But Hodaei’s work suggests that its deeper significance lies in the femininity embedded in the very concept of sofreh. Indeed, the messages of love and the blessings worked into these simple objects by the women who made them were aimed at bringing the family together. In other words, femininity seeks plurality and togetherness, and opposes violence and centralism. Thanks to these layers of hidden meaning, the simple spread becomes an iconic symbol. In the final, and most explicit, instalment of the series, The Empty Sofreh as a Diary, Hodaei recorded the events she witnessed between September and December 2022, when the protests in Iran reached their peak and normal life was no longer possible. Using thousands of tiny dots in vertical and horizontal lines, similar to the words in literary prose or the verses in a poem, she chron icled one event a day; each work therefore has a date and a title that refers to a specific incident. The idea to paint a kind of diary on empty tablecloths came to her when she saw students at the university who were protesting peacefully by sitting around an empty tablecloth, a symbol of life, blessing and freedom.